Today I’m honored to welcome guest blogger Leslie Draper from our Urban Light Community Church in Muncie, IN. Early in December, Leslie traveled to the border (along with Emilie Carpenter, also a member of Urban Light) to support those who are seeking asylum here in the United States. I know that this is a topic that has caused much debate and even vitriol in recent weeks and months in our country. I think Leslie’s first hand account is so helpful and most likely different from what we’ve been hearing from any news agencies. Her reflections are so powerful and poignant that I asked her permission to share this blog entry with the larger church body. We need to learn to listen more intently in moments like this, especially when we have sisters in Christ who have been there and witnessed things first-hand. I’m grateful for Leslie and Emilie and their willingness to go where few will actually go and I’m confident that many of us will find Leslie’s reflections incredibly helpful as we seek to make sense of difficult challenges like this one and how we can appropriately respond as followers of Jesus. I’m praying that the Spirit will give us eyes to see and ears to hear.

Christ’s Peace,

Lance

I wrote two blog entries on the experience of visiting the migrant caravan, the other of which can be accessed by clicking here. This piece is more of a spiritual reflection; the other is an informative call to action.

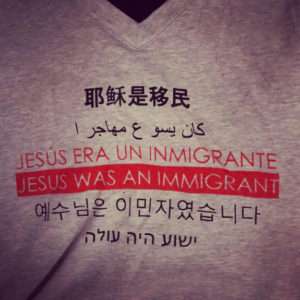

After a long journey, I met with a group of concerned citizens (primarily people of faith, led by Matthew 25 of Southern California) to cross the border to experience the conditions faced by the migrant caravan and received a t-shirt that said, “Jesus was an immigrant.” I was told I would come face to face with trauma in Tijuana’s migrant shelter, but I suspected I would be well-acquainted with the pain and harsh conditions and be able to process everything without too much shock. You see, secondhand trauma is a real and routine part of my life. I’ve learned to cope with it, on most days. I’ve learned to do all I can to alleviate the suffering of those around me and then check out and turn the situation over to God. I do this to keep my own savior complex in check and for the health and well-being of my family and I.

I really didn’t feel shocked by too much of what I experienced among the community of migrants this week. I was told to expect chaos, but what I experienced was anything but chaos. The migrant community was well-organized, and, well, a community. There was an atmosphere of mutual trust in the camp, without a lot of tensions that I could feel. There was an indoor shelter for women and families with children, but it was still just a huge room filled with tents (for those fortunate enough to get one).

The rest just had foam mats as their personal space on which to sleep with their belongings. As a woman, I can’t imagine actually sleeping enough to stay healthy. I’d feel like anyone could take advantage of me at anytime. I’d feel the need to stay half awake and on the alert at all times to protect myself and my children. I’d only sleep when my body could no longer keep going, and even then, only for a few hours at a time. As someone who needs plenty of alone time, I’d also lose significant psychological stamina. I found myself praying for the introverts in the room. As a matter of fact, one of the most disturbing pieces to me was the vulnerability of everyone in the camp, but especially the women and children. I played with a little, seven year-old girl for over an hour and never saw her parents. Such trust (or exhaustion) results in extreme vulnerability.

The pain and suffering of the people was intense because conditions were awful, and yet, thousands of people felt enough fear and desperation to choose the conditions of a refugee camp over their homes, their families, and the cultures in which they were most comfortable.

Quarters are tight, and this results in the spread of infectious disease quickly. And yet, in spite of all of this, people are banding together, organizing, and supporting each other as family. I guess I’m just not understanding why we as a nation are scared of these people. They are hurting, vulnerable people seeking safety. That’s all.

As I reflect twenty-four hours later, I find myself especially emotional because of my long-standing, deep relationship with Jesus. I began this blog entry by saying that I am well-equipped to turn off the pain of others’ trauma for the sake of my own emotional survival, but that is not the case when someone who is extremely close to me faces something awful. Yesterday, I saw a pregnant woman in the camp and thought, “Dear God, conditions at home must be awful to take on this journey pregnant. Where will she have the baby? When? Does she know she will have medical care and a sanitary place to give birth?” Today, after truly reflecting on Jesus as immigrant, I see Mary, the mother of Jesus, in this pregnant woman, and I want to weep. Yesterday, I saw a little baby laying on a mat beside his mother and marveled that someone with a new baby was making this journey, taking such risk with a new life, and I knew that meant the risk of staying felt greater to the mother than the risk of leaving her homeland. Today, I see the baby as Jesus, on a mat, in a refugee shelter, his mother and father fleeing for his safety, and I don’t know if I can stomach my pretty manger decoration when I get home. (Yes, there will be a manger scene in my house this year, but there will be conversations with my kids, and I will see Jesus in the migrant shelter in Tijuana.) I feel the pain of the people fleeing for safety as His family’s pain, and it brings it all to life in a way that rattles me just a little bit more. I learned more about God yesterday. I learned the story of Jesus and immersed myself in the Christmas story without even realizing it until later. The Holy Family fled political unrest and pursued safety in the more affluent Egypt (an economy, like the US, also built on the backs of slaves at one point in history). I, for one, am thankful that Egypt absorbed Jesus and his family into their economic and societal structures when they sought asylum. I hope we will think of this when we consider those seeking safety in our own country.